Kinda busy lately, so I am just going to keep reposting my old blog posts until they run out. Sorry!

This is a blog post from the past. Originally written at 2020-04-12.

John Conway, an extraordinary mathematician, passed away today due to covid-19. He is a great man and he inspired me to program. When I was small and I just got a phone, I found this game of life and I played with it a lot. It’s quite fun, as there are loads of results coming from such simple rules. And in memory of this great man, today we will implement this great algorithm made by John Conway himself: The Game of Life!

Introduction

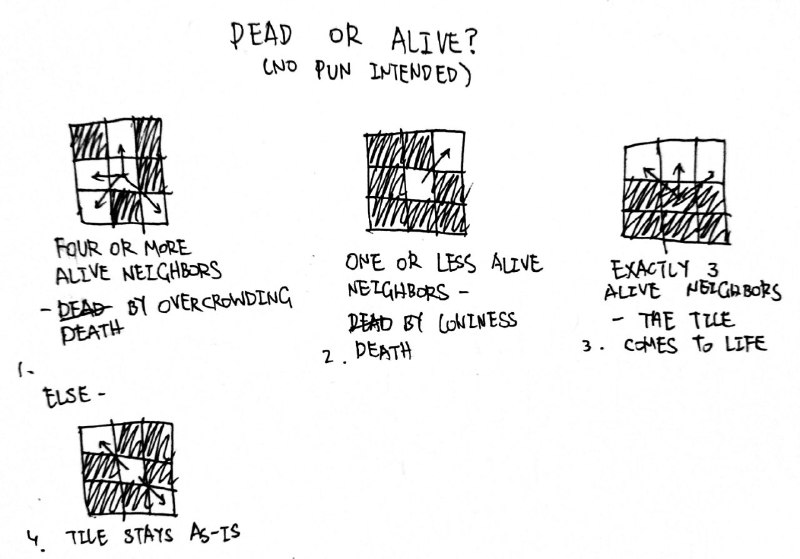

Game of Life comes with extremely simple rules. There are roughly 3 rules, I guess?

Each tile has two possible states: alive or dead.

- When a tile there are more than four neighboring tiles, this tile is considered dead by overcrowding.

- When a tile has less than one neighboring tile, this tile is considered dead by loniness.

- When a tile has exactly three neighboring tiles, this tile will become alive.

- Otherwise, this tile is kept exactly the state it was before.

If this still sounds a little bit ambiguous to you, let’s play with it for a little bit!

Play With It

Just paint above. The game itself will pause when you are drawing. The camera auto-focuses on a random alive tile. There’s nothing here for the moment. You can toggle the camera if you think it’s too shaky.

Implementation

So much complexity comes from such a small set of rules! Conway’s brilliant idea really made my day, especially when I was quite young, and get quite a bit of patience. I mean, there are a wiki dedicated to it. And we don’t need to know all the outcomes, knowing the rules only is good enough. To Conway!

I will give out vanilla browser JavaScript code this time, because I didn’t implement it in C/C++. I kinda rushed this, right after my last post. Anyway, here’s the first step, as per usual:

Initialization

So first, initialization. We are going for a dynamic, infinite map here, but if you want to do this the old way, of course you can do that too. Here’s what I did:

let grids = [];

We are going to represent each grid with a data structure so simple, I am not going to define it. And the data structure looks like this:

let grid = { x: 0, y: 0 };

When the grid is an alive grid, it will be stored in the grids array. If it’s dead, it won’t. And the initialization is done! What’s the most important comes after initialization, and that would be

Update

Updating the map is perhaps the most crucial part of the algorithm (duh). As we can see from this algorithm, only grids 1 tile close with currently alive grids have the possibility to be borned. As we are not keeping track of dead grids, we need to come up with a way to produce all potential alive grids:

function update() {

let potentials = [];

for (let i = 0; i < grids.length; i++) {

const g = grids[i];

potentials = potentials.concat(getNeighbors(g));

}

// additional code...

}

After this loop, the potentials array should contain all grids that are possible to prosper (or die). And here’s how getNeighbors should look like:

function getNeighbors(blockPos) {

function pos(x, y) { return { x, y } };

return [

pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y - 1),

pos(blockPos.x, blockPos.y - 1),

pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y - 1),

pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y),

pos(blockPos.x, blockPos.y),

pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y),

pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y + 1),

pos(blockPos.x, blockPos.y + 1),

pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y + 1)

];

}

Well, it is quite obvious that after doing this, there will be loads of repetitive grids. Thus we need a function to clean repetitive grids:

function cleanRepetitives(arr) {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

const pos = arr[i];

for (let j = i + 1; j < arr.length; j++) {

if (pos.x == arr[j].x && pos.y == arr[j].y) { arr.splice(j, 1); j--; continue; }

}

}

return arr;

}

function update() {

let potentials = [];

for (let i = 0; i < grids.length; i++) {

const g = grids[i];

potentials = potentials.concat(getNeighbors(g));

}

cleanRepetitives(potentials);

// additional code...

}

After cleaning, we need to iterate through all the potential grids, and check out their neighbors. As we are building the array for a new generation, we will need a new grid array. Let’s name it swap! I give bad names.

let swap = [];

for (let i = 0; i < potentials.length; i++) {

const g = potentials[i];

const n = getAliveGridNeighborCount(g);

if (n <= 1 || n >= 4) { setGridByPosition(swap, g, false); }

else if (n == 3) { setGridByPosition(swap, g, true); }

else { setGridByPosition(swap, g, findGridByPosition(grids, g) != -1); }

}

Well, this is really easy to understand, right? it dies when it is overcrowded or lonely, propagates if there are exactly 3 neighbors, and keeps how the way is otherwise. Now let’s implement those really simple functions:

function findGridByPosition(arr, blockPos) {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

if (arr[i].x == blockPos.x && arr[i].y == blockPos.y) { return i; }

}

return -1;

}

function setGridByPosition(arr, blockPos, state) {

let g = findGridByPosition(arr, blockPos);

if ((g == -1) == !state) { return; }

if (g != -1 && !state) { arr.splice(g, 1); return; }

arr.push({

x: blockPos.x,

y: blockPos.y

});

}

function getAliveGridNeighborCount(blockPos) {

function positive(pos) { return findGridByPosition(grids, pos) != -1 ? 1 : 0; }

function pos(x, y) { return { x, y } };

return positive(pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y - 1)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x, blockPos.y - 1)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y - 1)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x - 1, blockPos.y + 1)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x, blockPos.y + 1)) +

positive(pos(blockPos.x + 1, blockPos.y + 1));

}

And that’s pretty much it! Now finally, you just need to replace grids with swap:

let swap = [];

for (let i = 0; i < potentials.length; i++) {

const g = potentials[i];

const n = getAliveGridNeighborCount(g);

if (n <= 1 || n >= 4) { setGridByPosition(swap, g, false); }

else if (n == 3) { setGridByPosition(swap, g, true); }

else { setGridByPosition(swap, g, findGridByPosition(grids, g) != -1); }

}

grids = swap;

And that’s the whole package. It’s just an update, looping forever. The essence of life was shown from within, albeit deeply simplified. We are all dust! Life is meanlingless! Buy gold! Bye!

Conclusion

This is an easy algorithm, and I am just writing this to honor John Conway. He inspired me greatly on my coding career, and I am quite thankful of him. He is also a fun, witty man. May he live a good afterlife in the heaven! Goodbye, Dr. Conway! You will be missed. Stay home, wear mask, and wash your hands!

References

- Cellular Automation, Wikipedia

- Conway’s Game of Life, Wikipedia

- Does Conway Hates Game of Life?, YouTube

- LifeWiki

- John Horton Conway, Wikipedia

- The demo’s source tree (something might be different)

Comments